By Matthew Moorcroft

Highest Recommendation

- Directed by Hayao Miyazaki

- Starring Soma Santoki, Masaki Suda, Aimyon, Yoshino Kimura

- PG-13

Opening with a hospital fire, The Boy and the Heron (also known as How Do You Live? in it’s admittedly much better Japanese title) starts with a literal bang, which is interesting considering how much of The Boy and the Heron is also Hayao Miyazaki’s quietest film in a very long time. The legendary anime filmmaker has made it no secret that he has planned to retire for a very long time – seemingly every film he’s made since Princess Mononoke has been reported to be his last to some extent. But like every true artist, he just keeps coming back with something new to say, and every time it feels like this is his final statement.

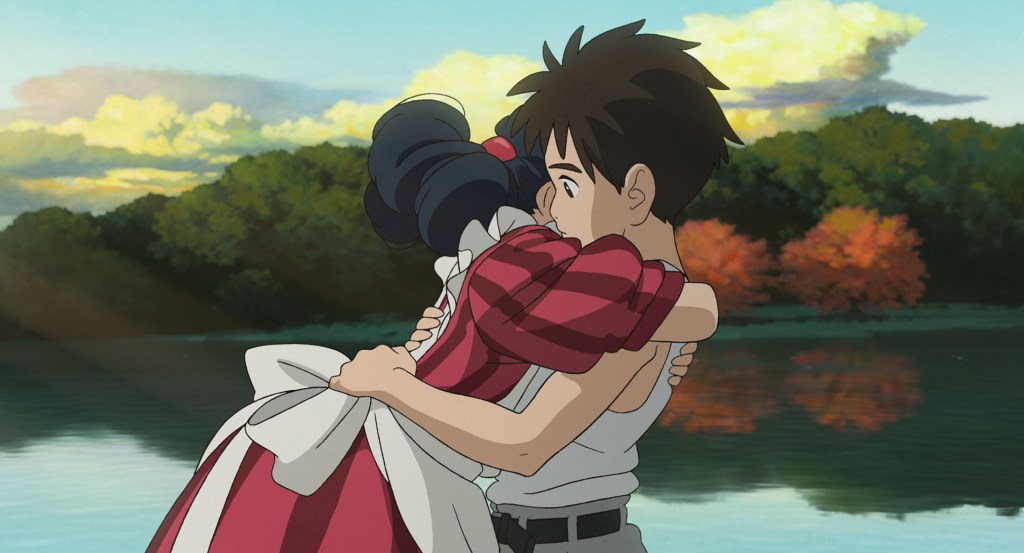

The Boy and the Heron is no different in this regard, but while The Wind Rises felt like Miyazaki’s attempt to outline his pacifist philosophy once and for all, The Boy and the Heron is much more complicated and fascinating. On the one hand, it’s a return to the genre that made him famous in the first – the big, mythic fantasy. This has more in common with Castle in the Sky or Howl’s Moving Castle then anything else, including a bit of a darker, more nightmarish Spirited Away or My Neighbor Totoro in there as well. For those who miss the fantastical Miyazaki, this is the film for you and you will certainly walk out satisfied.

On the other hand, The Boy and the Heron is also a dense work, much more so then usual for Miyazaki who tends to wrap up his more hefty narrative ideas in simple to understand concepts. The Boy and the Heron plays it entirely in metaphor and symbolism, however, and demands the audience’s full attention in order to process it’s exceptionally surrealist environment, narrative structure, and transitions. To give an example of how The Boy and the Heron works as a film, a great sequence involving a dying pelican (which occurs around halfway through the film) has very little in the way of narrative impact. It’s mostly there to give context to one prior scene, and even then feels almost like a sidetrack then anything in the film proper.

And yet, it’s in these scenes that The Boy and the Heron finds it’s groove and it’s beauty. Much of The Boy and the Heron is filled to the brim with gorgeous, luscious imagery that pops off the movie screen unlike anything you’ve ever seen before. The painted backgrounds and fluid, traditional cel animation – not done on computers like most 2D anime nowadays – give the film a texture that it otherwise simply wouldn’t have. But every single little diatribe and side quest, whether it be the dying pelican, an infiltration of a parakeet castle, or even the small day-to-day life of a new school year, is remarkably engaging and meaningful. It’s a film that feels painstakingly crafted even by Studio Ghibli’s already insanely high standards in that regard, with every single frame having been designed to possibly “be the last”.

To that end, it’s impossible to view the film as anything but the final manifesto of Miyazaki; a lay it all bare, full exposure of both his sensibilities as an artist but also as a deeply complicated human being. As the son of a father who he had himself a fraught relationship with – one he reportedly deeply regrets – and a strong opinionated mother who passed away when he was young, those deep wounds everywhere here. While our lead, Mahito, is very clearly a stand-in for Miyazaki himself, I really like to see him as Miyazaki’s younger self and the things that Miyazaki wishes he could have said and done. Beyond that self-reflection as well, it’s a deeply sad, melancholic film that ultimately makes the argument that life is only worth living if you ultimately die in the end, that the passage of time itself is what inherently makes things beautiful. Without that limitation, things become corrupt and violent.

Hayao Miyazaki is reportedly at work on his next film already, which shouldn’t be surprising given his track record, but if The Boy and the Heron ended up truly being his final film I don’t think I would mind. It’s everything his career has been building up to at this point and it only gets better the more you sit and ponder it. It’s a brilliant artistic achievement from a visual standpoint, and it’s also one of Miyazaki’s most deeply resonate, achingly personal works, and also one of the best films of the year.